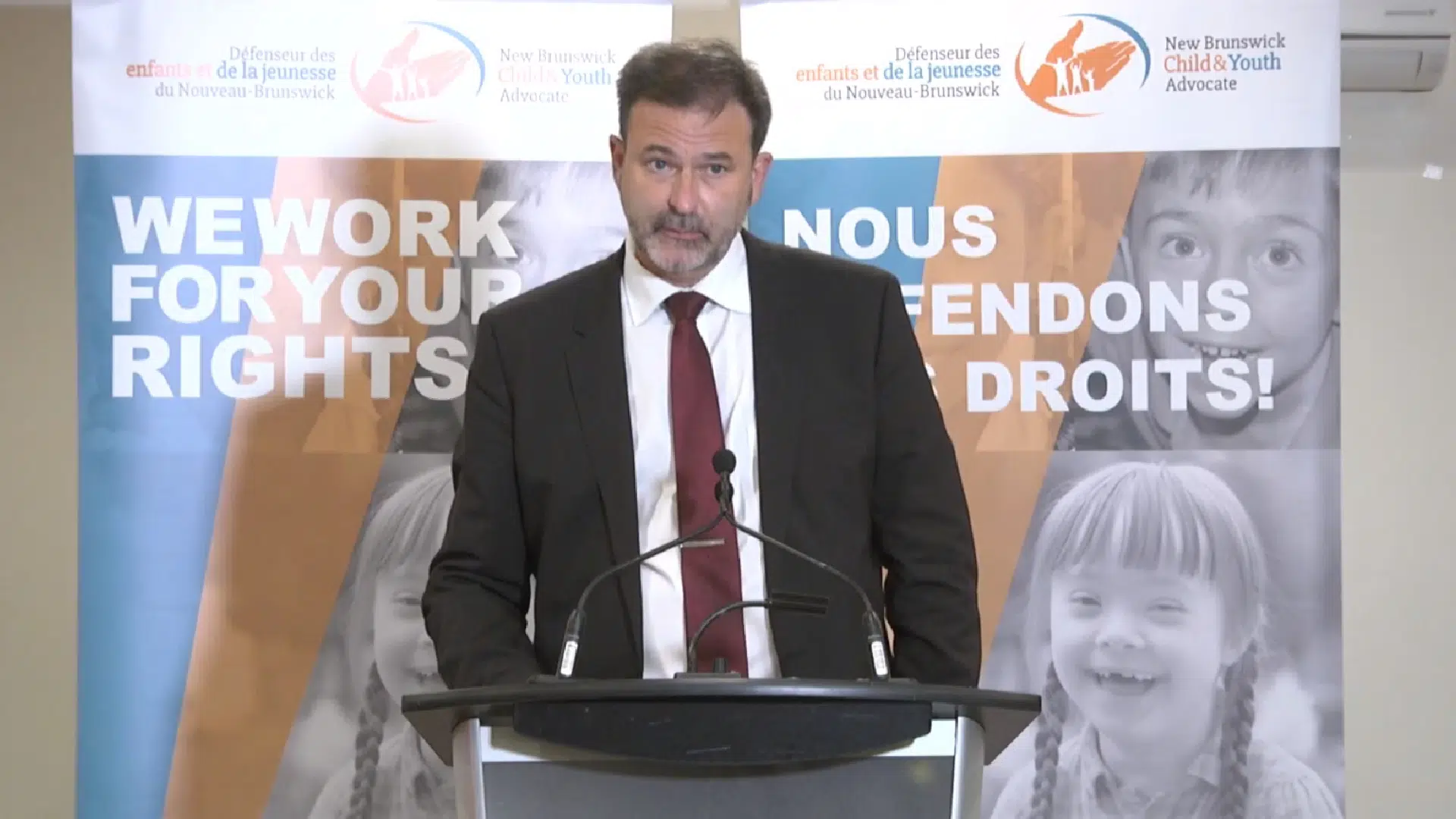

Christian Whalen, deputy advocate for the Office of the Child, Youth and Seniors' Advocate. (Image: livestream video capture)

New Brunswick’s child and youth advocate’s office released its annual snapshot Tuesday on how children in the province are faring.

The Child Rights Indicator Framework is usually released with the State of the Child report, but the office decided to release them separately this year.

It is described as a monitoring tool to help inform policy development that takes into account the lives, rights and interests of children and young people.

Deputy advocate Christian Whalen said in an interview Tuesday that the data continues to show some troubling trends in certain areas.

Whalen said his office has seen a significant rise in child protection caseloads, which they suspect was caused in part by the pandemic.

“We know that when there was a lockdown and kids weren’t in school and social workers weren’t as regularly accessible to them through the lockdown, that when schools opened up again, there was a huge uptick in the number of child protection reports,” Whalen said.

The office said it is concerned to know whether sufficient new resources have been applied by Social Development to meet the increased need.

Whalen noted that only 30 per cent of social workers were designated as essential during the recent strike by CUPE New Brunswick members.

“You try carrying on a child protection caseload any day of the week, let alone when two-thirds of your colleagues are on strike and you’re left to hold the fort. It’s just an impossible task,” he said.

Another trend Whalen described as troubling is that the year-over-year rate of teen pregnancy in New Brunswick remains well above the Canadian average.

“We’re asking questions about is this because we don’t have enough access to accessible abortion services in New Brunswick or is it because New Brunswick has made a different policy choice with respect to this social issue,” he said. “If it’s the latter, how do we make sure that the infants and the newborns that are born to these teen moms are getting all the supports and all the services that are going to put them on an equal playing field with their peers.”

But Whalen also pointed to some successes among the data, such as a downward trend with respect to the rate of pre-trial detention of youth, the rate of secure and open custody, and the overall youth crime rate.

There are also declines in hospital admission rates for youth mental health disorders.

“Instead of rushing to hospital when there’s a situation of crisis, we’re seeing a greater reliance on community-based care,” said Whalen.

The deputy advocate also noted that the pandemic hampered his office’s data collection efforts. He said many education sector data sets were incomplete due in part to the inability of schools to complete student wellness surveys last year.

“Pandemics are exactly the time when we need to be able to rely on good population health data. Moving forward, we urge the government to take effective measures to ensure the data collection efforts become a focus of pandemic preparedness planning,” said Whalen.

The release of the Child Rights Indicator Framework took place as part of Child Rights Education Week and leading up to World Children’s Day and National Child Day on Nov. 20.

Whalen said staff will continue to sift through the data and release more details as part of the State of the Child Report, which will be published in 2022.