The Atlantic First Nations Water Authority (AFNWA) has signed a framework agreement with the government of Canada to take over responsibility for water and wastewater services in at least 15 First Nations communities, including Elsipogtog in New Brunswick and Eskasoni in Nova Scotia.

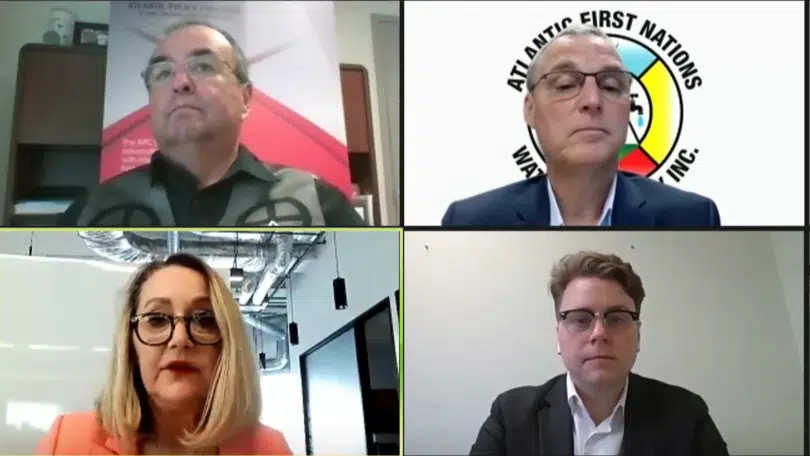

“Water is a keystone upon which prosperity rests. Progress is not possible if we can’t depend on water and water coming out of our taps safely,” says Chief John Paul, executive director of the Atlantic Policy Congress (APC), on Tuesday’s press conference.

“It will put Indigenous communities in control of one of the most basic needs, and give us the freedom to stop worrying about the safety of our water, and it will allow us to create our own path and our own destiny in a way that simply wasn’t possible before,” he added. “I am hopeful that what today means for our communities is access to clean drinking water, wastewater that will result in healthier outcomes for all our people.”

The APC was part of the First Nations Clean Water Initiative alongside interested First Nations communities and Indigenous Services Canada. That initiative led to the founding of the AFNWA in 2018 following a multi-year community engagement process that informed the authority’s hub-and-spoke structure. That structure allows for one anchor establishment (hub), complemented by operators in each of the communities.

“We will combine our resources, our operators will get familiar with each other’s systems in particular, and serve as a collective to optimize our processes around water quality and wastewater effluent quality,” said AFNWA’s interim CEO Carl Yates.

The First Nations-controlled water authority will support the 15 communities to upgrade, manage and maintain their water and wastewater services. It’s designed to be scalable, Yates said, so it could expand to include the rest of the 33 First Nations communities in Atlantic Canada, and so far, seven are on “hot standby.”

The framework agreement is the first for a First Nations-led water authority in Canada. It marks a milestone that allows AFNWA to take over responsibility and liability for water and wastewater services catering to over 4,500 homes and businesses on reserves – around 60 percent of the region’s First Nations population – from Indigenous Services Canada, which is investing $2.5-million to facilitate the move.

AFNWA aims to be fully operational by the spring of 2022. The utility is mandated to hire First Nations workforce “to the fullest extent possible,” Yates said, from CEO and other senior management staff to field operators. The search for the senior management team is underway to be in place by April 2021.

“All the assets will be transferred to the water authority to own and operate, and then by taking a direct look on the condition of all assets, putting together business plans, overtime, all of the infrastructure will meet the highest standards in the land,” Yates said. “We anticipate that this could be a journey of five-to-10 years to get everything in good shape. In particular, we’re going to see more investment in wastewater for sure.”

AFNWA will start its journey with the existing funding structure – 80 percent from the federal government and 20 percent from the communities. But Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller says “the idea is self-sufficiency” as part of Indigenous communities’ self-determination.

“These are slow, deliberate and important steps in getting out from under the Indian Act so to speak,” he said.

Yates said the AFNWA will operate in a way that combines science with traditional and cultural knowledge, as well as be environmentally responsible.

“We expect to look at a more holistic approach to ensure water quality is good from the source to the tap and back to the source again,” he said.

Chief Wilbert Marshall of Potlotek First Nations, Nova Scotia, is chair of the AFNWA board. He says his community has struggled with access to clean water for about 40 years. A new water plant is currently being built in Potlotek, and the AFNWA will take over ownership once it’s completed.

But Marshall says the plant has faced many hick-ups and delays. What was supposed to be completed last October is still being built today.

“I think if we had the water authority, none of this would have happened,” said Marshall.

He adds that it’s really important that this initiative is led and run by First Nations communities, and he clarified that the APC won’t be the one who “runs the show.”

“A lot of the time the government steps in and they give you no choice,” Marshall said. “But no, the way we see this, it’s going to be based on our guys, our communities, the experts in the field…the best water money could buy, for right now and the future of our communities, not just my community.”

The historical lack of access to clean water for First Nations, Metis and Inuit communities is a result of overt and systemic racism, Miller admits.

As of mid-February, some 61 Indigenous communities in Canada still faced poor water conditions or were under boiled-water advisories.

The lack of clean water, and other infrastructure such as proper housing and schools on reserves, have made Canada’s Indigenous communities more vulnerable to Covid-19.

Miller said it’s important to acknowledge and understand the existence of the systemic racism that led to that, but the pandemic has also become a time of reflection of the ways in which the government’s approaches to Indigenous communities have been “paternalistic” and “colonialist.”

“As we look towards the new normal post-Covid-19, in my mind, accelerating infrastructure builds, putting resources in place is where we ensure that First Nations…ensuring those inequities are closed,” Miller said.

While there are currently no long-term water advisories on public systems on reserves in Atlantic Canada, communities are still struggling with the quality of their water infrastructure.

“Work continues across the region to maintain and update water infrastructure to improve water quality or prevent future water advisories,” says Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller.

One of the issues with infrastructure maintenance and service delivery is the consistency of funding. The AFNWA removes year-over-year funding agreements towards long-term funding arrangements which can facilitate access to capital by the utility.

In the next couple of years, Yates said AFNWA will seek to establish policies for board governance, an asset management plan, and a 10-year capital budget and operational plan. They all need to converge with Indigenous Services Canada so there’s sustainable funding in place for the long-term, Yates said.

Miller said his department is open to funding this model in other regions if it works out, but it will be up to the communities how they want to manage their assets.

Inda Intiar is a reporter with Huddle, an Acadia Broadcasting content partner.